It’s every junior biotech company’s dream to be accepted into an accelerated approval pathway for a potentially blockbuster drug. Very few achieve it. Even fewer achieve two accelerated approval pathways for the same drug in two different regulatory jurisdictions. Going even further, how many get a multimillion dollar grant for the very pivotal trial meant to grant that accelerated approval?

Pluristem Therapeutics Inc. (NASDAQ:PSTI) has achieved just that, hitting for the cycle so to speak, with two accelerated approval pathways for its PLX-PAD placental cell treatment for critical limb ischemia (CLI). Back in May of 2015, Pluristem was accepted into the European Medicines Agency’s (EMA) Adaptive Pathways pilot project for this indication. The program allows for conditional approval based on limited data from a subpopulation of patients deemed to benefit most from an experimental treatment, followed by post-marketing expansion into wider patient populations.

The program itself is brand new, and in retrospect – the pilot stage of the project is now closed – has proven highly restrictive. Even the EMA itself did not know which companies it would accept and which not, and has only last week on August 3 published a hindsight report advising companies as to how to apply, which companies and indications have a better chance of acceptance, and general procedures to follow. By the end of the pilot stage, 62 applications were collected and only 6 accepted, for an acceptance rate of less than 10%.

As if that weren’t restrictive enough, in December of last year, Japan’s Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency cleared a Phase II 75-patient PLX-PAD trial for CLI structured for conditional marketing approval upon successful conclusion as well. This is a structurally similar approval pathway to the European Adaptive Pathways project that includes post-marketing approval expansion upon collection of further data.

Finally, piling on to Europe and Japan, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has also given its own green light to Pluristem on August 2 for the same drug in the same indication, using data from the very same trial as a Phase III pivotal. Practically, this means that two trials, one of 250 patients in the U.S. and Europe, and another of 75 in Japan, could clear PLX-PAD for marketing in three of the largest markets in the world in one stroke. All this, plus an $8 million grant from Europe’s Horizons 2020 program just announced for the U.S./European trial will fund most of it without Pluristem having to spend much out of pocket.

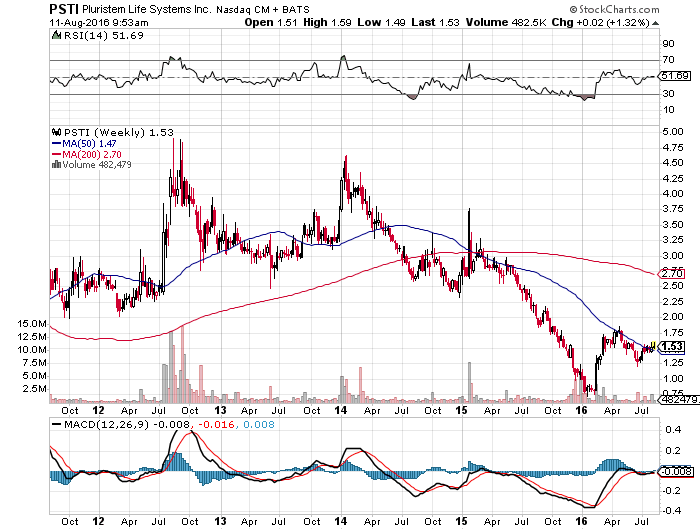

Why Pluristem Is Still Near Its Lows

While all this news is obviously good for the company, investors are nonetheless less than electrified, and for understandable reasons. Back in 2010, Sanofi SA (ADR) (NYSE:SNY) failed a promising Phase III CLI study for its drug called NV1FGF, even after positive Phase II results that were unfortunately not successfully replicated in the larger pivotal trial. This type of failure happens often, and could be behind why Pluristem’s share price has declined noticeably despite the spate of good news beginning in May 2015.

Sanofi vs Pluristem, Mirror Image Approaches to CLI

What investors should keep in mind though is that the approaches of these two CLI treatments are essentially opposing mirror images of each other in a manner of speaking, meaning the failure of one may not reflect on the other. NV1FGF was a DNA-plasmid delivered shot of an angiogenic growth factor, a gene therapy meant to induce the production of a factor that promotes the production of new blood vessels in affected limbs. CLI is basically the effect of a clogged cardiovascular system in the legs and feet, and it was theorized by Sanofi and its partners that promoting the growth of new blood vessels would create workarounds to the clogged network of veins and arteries. While Phase II was positive, Phase III unfortunately failed.

Pluristem’s PLX-PAD cells can be seen as the mirror image approach to NV1FGF in the following way. NV1FGF sought to isolate one factor by gene therapy to promote the growth of new blood vessels. The approach makes logical sense, but begins with a complicated procedure involving the identification and isolation of specific genes and delivery of these genes via plasmid DNA into the affected area. The genes must infiltrate cells, take over their machinery, and have them produce this specific factor to promote the genesis of new blood vessels.

PLX-PAD, on the other hand, is nothing but specialized placenta cells grown from actual human placentas. Rather than isolating specific genes to do a narrowly defined job of producing a single known angiogenic factor, infiltrate other cells and have them produce it, placental cells are already designed to promote the growth of new blood vessels by their very nature, and they do not generate an immune response, so need for genetic matching to patients. Nobody knows exactly how they promote new blood vessel growth, only that they do. After all, it is the cells of the placenta that guide fetal development, which includes growing an entire vascular system from scratch. So while NV1FGF isolates a specific factor by complicated genetic engineering, PLX-PAD takes the far simpler approach of making use of angiogenic growth factors within already functioning placental cells and simply injecting those cells, already equipped with the full machinery to promote angiogenesis.

If we call Sanofi’s approach the maximalist-minimalist approach for beginning with complicated engineering to produce a known mechanism of action, Pluristem’s approach would be the minimalist-maximalist approach, beginning with a simple procedure of growing cultured placental cells to induce a complex and generally unknown mechanism of action, but one that is known, from the nature of fetal development and birth itself, to consistently work in growing new blood vessels. Pluristem’s approach in a way lets nature run its course, while Sanofi’s attempted to isolate a specific mechanism from nature and use that to its advantage.

The process of fetal development and the effect that specialized placental cells have on this development not being well understood is, from one perspective, slightly nerve-wracking, especially for Pluristem and its investors. On the other hand though, the mysterious nature of these cells may have played a central role in getting Pluristem its $8 million grant in the first place. The grant is specifically designed to fund the trial itself as well as the study of PLX-PAD’s mechanism of action using a battery of immunological, endocrine, and molecular analyses to see what in fact is going on. Whatever this means, it does point to the fact that Europe is very interested in seeing why the initial Phase I trial results for PLX-PAD in CLI were so successful, especially in the U.S. trial.

Phase I Results

It was PLX-PAD’s Phase I results that were used as a basis of acceptance into the European Adaptive Pathways project and the Japanese accelerated pathways. In one of its most encouraging trials in CLI, there were zero cases of limb amputations or deaths during the 12-month follow‑up period after administration of these cells. Time to amputation or death was the primary endpoint in Sanofi’s pivotal trial as well, and the trial showed no statistical difference from placebo. A concurrent Pluristem European Phase I trial conducted in Germany showed a 73% amputation-free survival rate after 12 months, still higher than standard of care. If the two pivotal trials to be conducted can replicate these results, we are looking at a potentially blockbuster treatment for a $12 billion disease with no other treatment on the market other than manual surgical revascularization – essentially bypass or angioplasty surgery in the legs.

While Sanofi and NV1FGF have taught us to be cautious here, it is hard to discount these Phase I results entirely, together with the favorability Pluristem has enjoyed from regulatory authorities across the globe of late. It certainly makes sense to be cautious, but coasting along historic lows does not seem warranted given positive developments.

An Unmet Need

CLI may not sound as dreadful as a terminal disease like cancer for example, but the fact is that the mortality rate at 5 years post diagnosis is 50%, and 70% at ten years. From this perspective, CLI is practically a terminal condition at this point. It is an effect of general cardiovascular disease exacerbated by smoking and poorly-controlled diabetes. 53% of patients in Sanofi’s Phase III study were diabetics, and 47% had a history of coronary artery disease.

Extra $8M Further Pads Pluristem’s Balance Sheet

Prior to this grant by Horizons 2020, Pluristem already had about $40 million in cash and liquid assets. The grant brings the total to $48 million with an average quarterly burn rate of $5.6 million across the last four quarters. This gives them about two and a half years running room. The trials in both Japan and the dual pivotal trial in Europe and the U.S. are expected to be completed by 2018, and with enough cash to get there, it’s now only a question of whether Phase I results can be replicated in these trials. If they can, getting more cash will not be a problem.

The main risk, of course, is that they won’t be replicated, as happened to Sanofi. This is a legitimate worry for investors, but even so, does not seem to justify Pluristem being close to its lows with the amount of liquidity currently at its disposal and the array of regulatory perquisites it has received since last year in CLI. With liquidity at 40% of market cap, it does seem like the successes the company has had these last 15 months warrant more than a $76 million valuation excluding cash, especially considering the size of the CLI global market at $12 billion with virtually no competition.